History of the Tarawera Awa

Understanding where we have come from

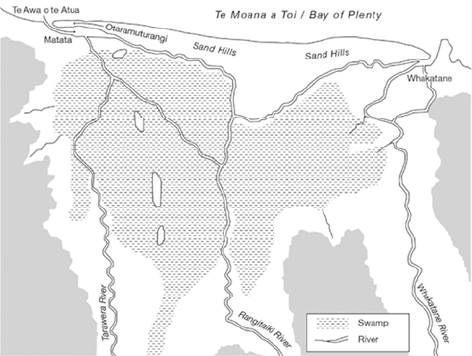

The river once flowed freely from its source at the Tarawera lake outlet, meandering northward feeding into life-enriched wetlands and tributaries along the way towards Te Awa o Te Atua. Water from Mount Tarawera and Pūtauaki, and geothermal water from Mangakotukutuku and Waiaute Streams feed into the Tarawera River, meeting the Rangitāiki River and Orini Stream before flowing to Mihimarino.

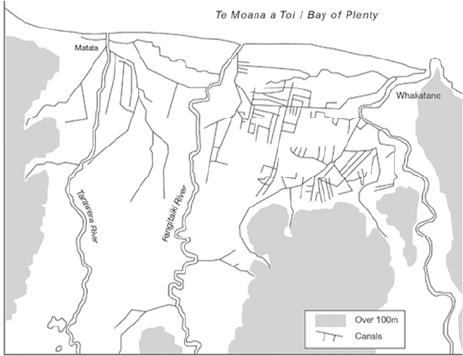

Motivated by the economic prosperity that increased land mass offered for settlers, the ancestral route was severed at its head in 1917 as part of the Rangitāiki Drainage Scheme, disconnecting the Tarawera from Te Awa o te Atua and the Rangitāiki river. A large network of canals and drains were constructed to drain the extensive former wetlands and create the Rangitāiki Plains to enable agriculture.

Before: Rangitaiki Plains pre-drainage. After: Rangitaiki Plains post drainage.

Altering the course of the Tarawera Awa had devastating economic, social, cultural and environmental impacts. It resulted in the significant loss of the port’s commercial opportunities and Te Awa o Te Atua’s food supply for the Iwi of Otamarorā – Matatā and left the once thriving estuary of Te Awa o te Atua stranded – no longer receiving the cleansing properties of Te Moana a Toi (ocean water) and no longer the meeting places of the Tarawera, Rangitāiki and Orini.

Over time, the health and well-being of the Tarawera Awa has been further jeopardised in pursuit of the economic benefits derived from the establishment of milling operations in Kawerau. In 1954 The Crown passed legislation freeing the mill from regular water pollution regulations. This allowed the mill to discharge waste into the Awa, causing severe pollution. The pollution was so significant that the water of the Awa was discoloured, giving rise to the nickname ‘the black drain’. In addition, the Tasman Mill also utilised Lake Rotoitipaku as the primary disposal site for liquid and solid waste.

As an iwi collective of the Tarawera Awa, we have inherited this legacy of degradation. Despite a solemn apology of the Crown for its historical failures in relation to the Tarawera Awa, the Crown is continuing to breach Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The Awa faces ongoing pollution through the issuing of resource consents permitting discharges. In 2009, further consents were granted to the Tasman Pulp and Paper Mill operators, which permitted them to discharge waste into the Awa for a further 25 years.

These discharges may be at levels that are considered less physically harmful than the toxic discharges of the 20th century, however, the mauri of the Awa suffers not just physically but spiritually from these offensive discharges, regardless of the perceived level of toxicity assessed through a Western scientific lens. This fundamentally fails to meet the high standard for active protection and recognition of iwi rangatiratanga.